From Rosie the Riveter to the Global Assembly Line: American Women on the World Stage

Drawing Closer Together

In 1939, shortly after the outbreak of war in Europe, American pacifist and feminist Emily Greene Balch wrote from Geneva to colleagues in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) about their plight. "Ringed around by a wall of violence, we draw closer together" 1. It was a hopeful statement about organizational and gender solidarity in the face of impending doom, but it can perhaps also serve as a foreshadowing of the ways that, in the more than half century since the end of World War II, women across the continents have at times been able to make connections across national differences to confront common problems, including gendered violence. From a twenty-first century vantage point, we can look back over the decades and see how intimately connected the changes in American women's lives have been with events unfolding on the world stage and how little of what happens to women in the United States is unconnected to larger global forces.

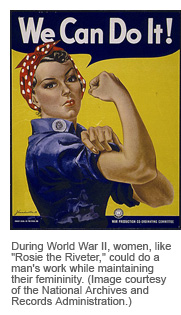

The magnitude of the worldwide conflict that ended in 1945 with the surrender of Germany and Japan, the liberation of the concentration camps, and the unleashing of the atomic bomb had brought American women, like women elsewhere, into areas of the labor force previously reserved for men. Like Rosie the Riveter, the symbol of American women patriotically taking up factory jobs previously reserved for men, women in all of the combatant countries went to work as men left to fight. Women even made inroads into the armed forces, although not, in the United States, as combatants. Spared the devastation of bombed-out cities and the massive losses suffered by the peoples of Europe and Asia, Americans set about reestablishing "normal life," although in a vastly reconfigured global context. Men returning home sought both their jobs and the comforts of a wife at home, if they could afford it. Although many women who had moved from poorly paid service jobs into more financially rewarding factory jobs preferred to remain, employers moved to restore the prewar sexual division of labor. In fact, even as increasing numbers of white middle-class women were entering the paid labor force in the postwar years, the goal of returning women to the home became a hallmark of American life, in contrast to the Soviet-bloc countries, where women were encouraged to combine paid work and motherhood. Equally striking was the fact that the American occupation authorities in both Germany and Japan, assuming that women could serve as the foundation of democratic governments, insisted that those countries' new constitutions grant women equal rights, while the Equal Rights Amendment at home languished in congressional committees.

In the context of the Cold War that followed closely on the heels of the end of hostilities, differences between the Soviet employment of women, especially in factory labor, and American domesticity took on political and diplomatic importance. Symbolic of this cultural clash was the famous "kitchen debate" between U.S. vice president Richard Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1959 at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow. Nixon praised capitalism for providing U.S. housewives with an array of consumer goods and the choice of brands of appliances, while Khrushchev, although also touting domesticity, boasted about the productivity of Soviet women workers. It was a debate that laid bare the ideological and economic differences between the two systems as they competed for dominance in the world system.

One way that rivalry played out was in competition for the hearts and minds of what came to be known as the "Third World." Just as the two superpowers raced to try to make over in their own image countries newly independent of colonial rule, so too did transnational women's organizations from each bloc seek to bring developing countries into their fold. The new Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF), launched out of the Communist-led resistance movements of World War II and dominated by the Soviet Union, challenged the traditional transnational women's organizations such as the International Council of Women, the International Alliance of Women, and the WILPF and competed with them at the United Nations over who really represented the world's women. The older organizations, dedicated to women's rights and peace, had long sought to make their membership "truly global" but remained dominated in terms of membership and leadership by women from western and northern Europe and the United States. The WIDF, in contrast, although founded in Paris and supported from the Soviet Union, won adherents throughout the Third World through its commitment to "win and defend national independence and democratic freedoms, eliminate apartheid, racial discrimination and fascism"2. In the United States, organizations associated with the WIDF found themselves accused of Communist affiliations in the postwar crackdown.

The decade of the 1950s has indeed gone down in American history as Nixon depicted it to Khrushchev—a period of prosperity, conformity, domesticity, and suburbanization. Retreating from the disruptions of war and threatened by Soviet expansion and Chinese revolution without and Communist subversion within, Americans, according to the conventional story, clung to home and family life. White men, taking advantage when they could of mortgages and college educations made possible by the GI Bill, became "organization men" loyal to their corporate employers and took up "do-it-yourself" projects in their suburban homes on the weekends. White women stayed home in the expanding suburbs, giving birth to more children and drinking coffee with their neighbors. Such prosperity depended on U.S. domination of the world economy in the aftermath of the war. Suburban mothers chastised children reluctant to clean their plates to "think of the starving children in Europe"; with European economic recovery, the line shifted to the starving children in Africa. When Michael Harrington published The Other America in 1962, the fact that poverty existed at home came as something of a shock to those not experiencing deprivation themselves. A decade later, the revelation of the "feminization of poverty" both in the United States and globally called attention to the economic impact of discrimination against women, the sexual division of labor, the wage gap between women and men, and women's responsibility for rearing children.

Uniting Against Discrimination

Just as the reality of poverty underlay American prosperity in the 1950s, so too was the domesticity and tranquility of the 1950s far more apparent than real. In the burgeoning civil rights movement, African American women and men organized their communities and launched determined protests against segregation and discrimination, taking heart from national liberation movements in Africa and elsewhere. From the group of mostly mothers whose challenge to the segregated school system of Topeka, Kansas, contributed to the Supreme Court decision declaring segregation inherently unequal in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) to Rosa Parks, who refused to move to the back of the bus in 1955 and helped launch the Montgomery bus boycott, black women played critical roles in calling the attention of the country and the world to the second-class status of African Americans. In the West, Mexican American working-class women and men also took up civic activism on the local level, like African Americans inspired by nationalist movements in the Third World. Within the beleaguered union movement, in the peace movement, in the remnants of the women's movement, in the vilified Communist Party, in the homophile movement that sought acceptance for lesbian and gay Americans, women fought for social change despite the proclaimed contentment of the era.

The recognition that a great deal was going on beneath the surface calm of the 1950s goes a long way toward helping us understand the origins of the explosive decade of the 1960s. The social protest movements of the 1960s had their roots in the tensions and contradictions of the 1950s. But they also occurred in a global context, as national liberation movements increasingly freed former colonies from the grip of imperialism. Transnational connections can be glimpsed in Martin Luther King, Jr.'s embrace of Gandhian nonviolence, while Gandhi himself used tactics in the Indian struggle for independence inspired by militant British women fighting for the right to vote. Or in the anthem of the civil rights movement, "We Shall Overcome," with origins in the "sorrow songs" of slaves brought from Africa, then sung by striking tobacco workers in the 1940s, and then sung in Arabic by Palestinians, in Spanish by members of the United Farmworkers, and, in a sense going home, in the South African antiapartheid movement.

Social upheavals occurring across the globe made the year 1968 synonymous with struggles for social justice. It was in 1968, when French students threw up barricades in the Left Bank quarter and protesting Mexican students were gunned down by the government, that a group of feminists gathered in Atlantic City to protest the objectification of women in the Miss America Pageant. In what has become a legend in the history of the resurgence of feminism—and what gave rise to the mistaken notion that feminists burned their bras—feminists dumped bras, corsets, and hair rollers into a "freedom trash can" and crowned a sheep Miss America.

The turmoil of the 1960s sparked renewed activism by women all around the globe, although feminist movements almost everywhere had roots reaching back to earlier struggles by women for education, civil and political rights, employment opportunities, and other legal and social changes. Sometimes, as in the United States, women in male-dominated social justice movements began to adapt class or national or racial/ethnic critiques to their own situation as women, particularly if they found themselves pushed aside or relegated to second-class citizenship after fighting alongside men for freedom and justice. Although women's movements took on different shapes in various parts of the world—liberal feminism calling for the extension of the rights of men to women, socialist feminism advocating revolutionary change, radical feminism challenging the devaluing of women and the exploitation of women's sexuality and reproductive capacity—feminist movements growing from indigenous roots and influenced as well by a transnational exchange of ideas and strategies flourished. Feminism as a world view emphasizing the equal worth of women and men; a recognition of male privilege; an understanding of the ways that gender intersects with race, class, ethnicity, sexuality, ability, and other forms of difference; and a commitment to work for social justice found footholds everywhere. In different contexts, women organized and fought for access to education and employment, for control of their bodies, and against various forms of violence against women, including in wartime.

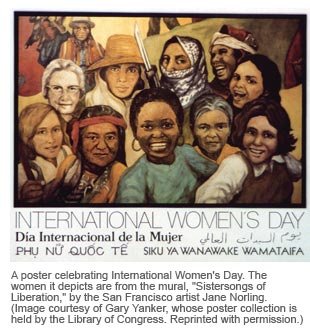

In the United States, African American, Latina, Asian American, and Arab American women, often angered by the white, middle-class assumptions of women's movement groups, connected their struggles to those of women in the Third World, taking on the term "Third World women" to describe themselves. Under the auspices of the United Nations, which included the principle of equality between women and men in its charter from its founding, women from across the globe came together in a series of conferences. A meeting in celebration of International Women's Year in Mexico City in 1975 gave rise to the UN's "Decade for Women," marked by a gathering in Copenhagen in 1980, and Nairobi in 1985, followed up by a fourth international conference in Beijing in 1995. From the beginning, conflicts erupted among women. In Mexico City, Domitila Barrios de Chungara, representing an organization of Bolivian tin miners' wives, expressed shock at discussions of such issues as prostitution, lesbianism, and male abuse of women, arguing that women in her group sought to work with men to change the system so that both women and men would have the right to live, work, and organize. In these meetings, the diverse lives of women came to light and made clear the need to broaden the definition of what counted as a "women's issue."

These international meetings brought together not only official government representatives but, more productively, auxiliary forums of nongovernmental organizations. There debates about the impact of development policies, poverty, welfare systems, population policies, imperialism, and national liberation movements on women raised consciousness among women in the United States and other industrialized nations. Women from the global South voiced criticism of the narrowly defined interpretation of gender interests often articulated by women

from the affluent North in a way that resonated with the critiques of women of color in the United States. What difference does the "glass ceiling" that keeps U.S. women from reaching the top rungs of their professions make to women who have no right to land and cannot feed their families? And perhaps more troubling, who is making the clothing worn by professional women in the industrialized countries, who is cleaning their houses and caring for their children, and under what conditions? The United Nations nongovernmental gatherings helped to articulate the multiple ways that the experiences of women of different nations were intertwined, from Asian and Latin American women producing clothing and electronic products on the global assembly line for purchase by U.S. women to the international sex trade that makes prostitution and the "entertainment industry" a major employer of women in a number of Asian countries, to the immigration of women from the Philippines, Mexico, and Latin America to work in U.S. and European homes as maids and nannies while forced to leave behind their own children.

As the twentieth century drew to a close and the Cold War ended, the world had come a long way from the "kitchen debate" of 1959. By the dawn of the new millennium, the divisions between the global North and South had superceded the old political rivalries, and the question of globalization's impact on women came to the fore. What happens to women's traditional work in agriculture or trade when international lending agencies require a country to gear its economy for the world market? Where does "surplus" female labor go? Connecting such questions to the employment of women in sweatshops, as domestics, and in the sex tourism industry makes clear the impact of large-scale forces on women's lives and the ties that bind women in developing countries to those in wealthy industrialized ones like the United States. The pressing questions for women all around the world are what kinds of work they do, how much they are paid, what kinds of opportunities are open to them, who does the housework and takes care of the children, how much control they have over their sexuality and reproductive capacity, who makes decisions for the family and nation. These are the questions with which transnational feminism grapples. All point to the interconnections of gender, class, race, ethnicity, sexuality, ability, and nation. In a world in which we are still, as Emily Greene Balch lamented, "ringed around by a wall of violence," hope lies in the connections American women can make with each other and with women around the globe.

Endnotes

1 Emily Greene Balch to International Executive Meeting, November 21, 1939, WILPF papers, reel 4.

2 WIDF Constitution, quoted in Cheryl Johnson-Odim and Nina Emma Mba, For Women and the Nation: Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti of Nigeria (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 137.

Sources

Evans, Sara M. Tidal Wave: How Women Changed America at Century's End. New York: Free Press, 2003. An examination of the U.S. women's movement that emphasizes the diversity of participants, the geographical spread of activism, and the continuity of struggle.

Ferree, Myra Marx, and Beth B. Hess. Controversy and Coalition: The New Feminist Movement Across Four Decades of Change. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2000. A comprehensive sociological survey of the U.S. women's movement, tracing its development over time and its changing structure and strategies.

Freedman, Estelle B. No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women. New York: Ballantine Books, 2002. An analysis of the women's movement in global perspective, surveying the emergence of feminist movements; their varied approaches to work, family, sexuality, politics, and creativity; and the diversity of views and participants that ensures the continuation of feminist struggle.

Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Zed, 1986. A classic work on the history of women's political struggles in Asia and the Middle East since the late nineteenth century, arguing that feminism has indigenous roots throughout the Third World.

Johnson-Odim, Cheryl, and Nina Emma Mba. For Women and the Nation: Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti of Nigeria. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997. A biography of a Nigerian activist involved with women's issues in her own country and transnationally through the Women's International Democratic Federation.

May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988. An analysis of the ways that the Cold War affected all aspects of American women's lives in the 1950s, from sexuality and reproduction to consumerism and family life.

Meyerowitz, Joanne, ed. Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945-1960. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994. A collection of essays on diverse women's activities in the United States in the 1950s that explodes the myth of domesticity and contentment.

Miller, Francesca. Latin American Women and the Search for Social Justice. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 1991. A history of women's organizing in Latin America that includes Latin American women's involvement in international women's movements.

Naples, Nancy A., and Manisha Desai, eds. Women's Activism and Globalization: Linking Local Struggles and Transnational Politics. New York: Routledge, 2002. A collection of essays dealing with contemporary women's activism in opposition to the consequences of globalization.

Richardson, Laurel, Verta Taylor, and Nancy Whittier, eds. Feminist Frontiers. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004. A women's studies text that includes articles detailing diverse women's experiences with appearance, socialization, work, family life, sexuality, reproduction, violence, politics, and the women's movement.

Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women's Movement Changed America. New York: Viking, 2000. A comprehensive study, based on oral histories and archival research, of the women's movement and its impact on American society.

Rupp, Leila J. Worlds of Women: The Making of an International Women's Movement. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997. A history of the first wave of transnational organizing among women from the 1880s to 1945, focusing on the International Council of Women, the International Alliance of Women, and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

Smith, Bonnie G., ed. Global Feminisms Since 1945. London: Routledge, 2000. A collection of essays focusing on women's movements in different parts of the world.

Multimedia

United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women. Women Go Global: The United Nations and the International Women's Movement, 1945-2000. CD-ROM. United Nations, 2000. An interactive CD-ROM on the events that have been shaping the international agenda for women's equality since the founding of the UN.

Leila J. Rupp is a professor and chair of Women's Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. A historian by training, her teaching and research focus on sexuality and women's movements. She is coauthor with Verta Taylor of Drag Queens at the 801 Cabaret (2003) and Survival in the Doldrums: The American Women's Rights Movement, 1945 to the 1960s (1987) and author of A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Sexuality in America (1999), Worlds of Women: The Making of an International Women's Movement (1997), and Mobilizing Women for War: German and American Propaganda, 1939-1945 (1978). She is also completing an eight-year term as editor of The Journal of Women's History.

Authored by

Leila J. Rupp

University of California

Santa Barbara, California