Race and Citizenship

Conceptual Companions

At first sight, the concepts of race and citizenship might seem to be at odds with each other. Citizenship is premised on individual equality, while the essence of race is collective inequality. Citizenship is celebrated as a cultural achievement, the hallmark of a developed stage of civilization, while race is held out as a preeminently natural condition. Despite these differences, however, the modern concepts of race and citizenship emerged in close historical proximity to each other, and they have been constant companions ever since, so we should look beyond the semblance of inconsistency to seek the basis for their compatibility. This article will propose that race restored the social inequality that citizenship had theoretically abolished. Moreover, though the concepts of race and citizenship have varied considerably across time and space, race has generally operated to reconcile the contradictions between official rhetorics of citizenship and the practical continuation of social inequality. To illustrate these contentions, we will compare the U.S. experience with examples drawn from the histories of Australia and Brazil.

The interchange between race and citizenship is particularly apparent in societies, such as the U.S., Australia, and Brazil, that originated as settler colonies and continued to rely on large-scale immigration for their expansion and development. Colonial settlers sought to replace indigenous social institutions with their own, which they had brought with them from Europe. Over time, however, the same settlers came to assert their independence from the mother country. Thus the forms of citizenship that emerged in concert with the new postcolonial polities were new in relation both to native societies and to the European metropolis.

To facilitate the replacement of native social institutions, settlers sought to distinguish themselves ethnically, physically, and culturally from the natives. The rules that applied to Europeans would be different from those that were appropriate for the natives. In this connection, race differentiated fundamentally between natives and Europeans. Race also served to classify the waves of immigrants, whom it variously included or excluded from the ranks of the citizenry. In the U.S. and Brazil, variants on the general theme of race also served to legitimate the enslavement of people of African descent.

Race in American History

In the U.S., the relationship between race and citizenship was further complicated by federalism. The federal system that was created by means of the Constitution produced continuing controversy as to whether "we the people" were first and foremost citizens of the U.S. or first and foremost citizens of their particular states. This difficulty was greatly exacerbated by the North/South division over African Americans' membership of the sovereign community, a division that was only resolved through bloodshed. Even in the antebellum North, blacks were subject to a range of civic disabilities that varied from state to state but that rendered their citizenship lower than that enjoyed by whites. Nor was the issue of black people the only ethnic question to complicate the operation of citizenship in the early republic. In the wake of the Revolutionary War, the victorious colonists, who saw themselves as restoring and extending freedoms that had fallen into abeyance under the corruptions of the English crown, were not generally disposed to grant immediate citizenship to immigrants who had not been born in the country, who were not familiar with the concepts or the practice of responsible self-government, and who had not risked their lives and property to secure the nation's freedom. From the beginning of the republic, therefore, citizenship was a controversial institution whose rhetoric of individual equality contrasted with practical exclusions and distinctions.

In the wake of the Revolutionary War, race and citizenship remained closely tied together, but their nature changed in relation both to each other and to the changing demographic and political circumstances of U.S. society. The original concept of citizenship as a grouping of equal individuals restricted membership to white males. At the outset, therefore, citizenship was defined by race and gender. Native Americans, black people, and white women were not included. Moreover, the definition of white was Anglo-Protestant. Over time, all this would change. In particular, the impact of immigration was profound. To save the citizens from becoming outnumbered by a combination of black people, Asians, and immigrants, citizenship was made more inclusive. At various stages in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the definition of white was expanded to include Catholics, Jews, Irish, Mediterranean peoples, and even Hindus, so that large numbers of people who would not have qualified to be citizens in the early republic became citizens as a result of definitional shifts.

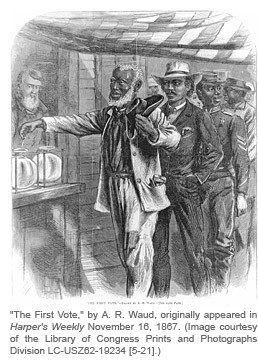

After the Civil War, when citizenship was extended to black people (as distinct from their partial enfranchisement in the antebellum northern states), there was a significant change, with black leadership emerging in southern states with majority black populations. The reaction against Reconstruction was thoroughgoing and ruthless, however, with black people's formal citizenship being mercilessly devalued in the Jim Crow era. Indian people, with individual exceptions, generally remained outside the domain of citizenship until after World War I. By this stage, however, continuing large-scale immigration had resulted in the inclusion within the ranks of the citizenry of large numbers of groups whom Anglo-Americans did not practically regard or treat as equals.

Accordingly, by the early twentieth century, the concept of an equality of individuals in the U.S. had begun to shift towards the notion of a hierarchy of unequal ethnic groupings. Citizenship was becoming collective and uneven. On this basis, there was a place for Indians too, as another collective grouping among many within an unequal hierarchy. In 1924, citizenship was extended to all Indians. Under the New Deal, the tribes came in from the cold, being politically included and regulated under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. In the wake of World War II, further shifts in the conceptualization and gradations of U.S. citizenship, especially where black people were concerned, reflected the impact of the civil rights movement, the cold war, continuing nonwhite immigration, and multiculturalism. More recently, the so-called "war on terror" would seem to be bringing about further changes to the mosaic of U.S. citizenship.

Science and the Concept of Race

Against the shifting ground of citizenship, the concept of race was also unstable. As observed, the historical development of the two concepts was closely linked. Both came to fruition in the eighteenth century, and were particularly associated with the Enlightenment and with the American and French revolutions. To say that we can date the emergence of the idea of race from this era, however, is not to suggest that Europeans had previously failed to recognize and act on observable phenotypical differences. Precursors are legion. One only has to cite Othello. Yet the mere fact that people have differentiated between human collectivities does not mean that they have subscribed to the ideology that today we call "race." (It would be hard to establish a connection between Othello and the bell curve, for instance*). The idea of race is but one historically distinctive mode of collective differentiation. Though most if not all of its ingredients can be found in earlier classifications, race combined these elements into a particular ideological mix that was not found before the eighteenth century.

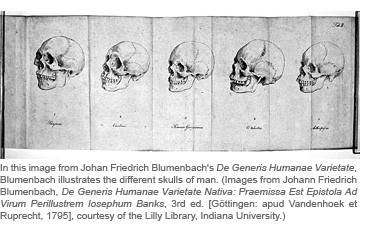

The science of race originated as comparative craniology, which received its first systematic expression in 1795 with the publication of the third edition of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach's De Generis Humanae Varietate, in which Blumenbach categorized humanity, in the taxonomic manner of Linnaeus and Buffon, as a single species divided into five varieties (Caucasian, Mongolian, Ethiopian or Negroid, American, and Malay). These varieties were distinguished according to the criteria of hair type, color, body structure, and, especially, the shape of the skull as viewed from above (the norma verticalis). From here, it was a short step to the invidious hierarchies of nineteenth-century scientific racism.

But race was more than just science. The feature that sets the concept apart from other ideological constructs is that it reconciled the great taxonomies of natural science with the political rhetoric of the rights of man. The prestige of natural science lent authority to a contradictory ideology that tolerated the enslavement of Africans as a condition of American freedom. As Edmund Morgan and other U.S. historians have shown, the concept of race enabled slaveholding founding fathers such as Washington and Jefferson to proclaim universal liberties without apparent embarrassment. In the nineteenth century, a hodgepodge of scientific theories was used to bolster racial discrimination. The doctrine of polygenesis, for instance, held that black people and Indians were separate species to white people, descended from "different Adams." As such, they were entitled to different standards of treatment. As the nineteenth century wore on, an assortment of scientific variations on the doctrine of progress hardened into a consensus generally known as Social Darwinism, whereby nonwhite races were seen to be held back at various stages in the evolutionary history that Europeans had already passed through. Accordingly, nonwhite people were congenitally inferior to whites, whose mission it was to govern and uplift them. The bell curve has a long history.

Social Darwinism was equally influential in nineteenth-century Australia. Rather than providing a justification for enslaving Aboriginal people, however, the doctrine was used to explain their disappearance. Aborigines were held to be denizens of the old Stone Age. In the form of whites, they were encountering their immeasurably distant future, a people who had been selectively made fit by millennia of progress. Accordingly, it was inscribed in the natural order of things that Aborigines would simply fade away—their decimation was not their white invaders' fault. Though premised on the same body of doctrine, therefore, the racialization of black Australians assigned them a destiny that was very different from the one that was prescribed for black people in the U.S. Yet it was very similar to the destiny that U.S. racial ideology assigned to Indians, who were, of course, classified as red rather than black.

When it comes to the practical aspects of the racialization of subordinated social groups, therefore, we need to look beyond natural-scientific categories (color, genes, bodily characteristics, etc.) to the social contexts in which the idea of race was activated. In this case, it is clear that the distinction between native peoples and those who have been enslaved is crucial. It is also clear that both racialization and admission to citizenship are significantly determined by the relative numbers of the populations concerned.

Global Comparisons

In Australia and in the U.S., white authorities have generally accepted—even targeted—native people's physical substance (typically represented as blood) for assimilation into their own stock. In both countries, native people have resisted assimilation, asserting criteria other than blood quanta as bases for group membership and identity. When it has come to black people's physical substance, on the other hand, it has only been in the past few decades that U.S. authorities have dispensed with the most rigorous procedures for insulating the white bloodline. Moreover, with some exceptions, black groups in the U.S. have themselves affirmed the "one-drop rule," maintaining an inclusive membership policy that, apart from anything else, has kept up group numbers. For black Americans, the descendants of slaves, race has operated to separate and differentiate them from whites. Thus the admission of black people to citizenship, which theoretically proclaimed their equality with whites, produced a crisis that opponents of black rights sought to resolve by dramatically intensifying racial boundaries. By contrast, citizenship for Indian people culminated a campaign of assimilation that had sought to absorb them into, rather than differentiate them from, white society. It is highly significant that, though Aboriginal people in Australia are classified black, their racialization should resemble that of Native Americans. Native Americans and Aboriginal Australians are numerically small indigenous groupings as opposed to numerically significant descendants of slaves.

The contrast with the Brazilian experience is illuminating. In Brazil, the descendants of slaves constituted a substantial majority of the population. In contrast to the one-drop rule—which, in the U.S., unified and excluded the black community—Brazil developed a complex set of color classifications whose effect was to break up and divide the Afro-Brazilian population, which had acquired citizenship on the abolition of slavery in 1888. Moreover, under the official policy of "whitening," the Brazilian government combined a strategy of importing large numbers of white immigrants with a campaign designed to breed out the black population through systematic miscegenation. In Brazil, therefore, where black people's numbers were much higher than in the U.S., racial discourse came to resemble the assimilatory policies applied to indigenous people in the U.S. and Australia.

In the U.S., the policy of assimilating Indians culminated in 1924, with the passing of the act that extended citizenship to all Indians. Strikingly, 1924 also saw a high-water mark in Jim Crow racial codification in the form of the Virginia antimiscegenation statute, which barred white people from marrying other than white people. As if to dramatize the discrepant ways in which blacks and Indians were being racialized, however, this act conceded the so-called Pocahontas exception, whereby certain categories of white/Indian unions were specifically exempted from its otherwise draconian catalog of proscriptions.

For Indians, citizenship and racialization converged. Both conduced to assimilation, the ultimate and least redressable mode of elimination. Conversely, rather than converging with their citizenship, black people's racialization could not have conflicted with it more violently. The racist terror of Jim Crow was above all directed towards undoing the formal equality that black people's citizenship entailed. The difference could not be clearer. Black people did not have to be rendered equal to be exploited. Their inclusion would not add millions of acres to the national estate.

Thus we return to the question of equality, and the relationship between citizenship and race. I propose a modification to Edmund Morgan's analysis of the relationship between race and slavery. As Morgan showed, the idea of race provided white men with an alibi for slavery. When that idea first emerged, therefore, it was secondary to slavery, for which it furnished a justification. With slavery in place, full-blown racialization was relatively redundant. Prior to emancipation, which occurred piecemeal in the northern states well before the Civil War produced the final emancipation of slaves in the South, the juridical condition of slavery had not been absolute. In particular, manumissions had taken place on an individual basis. By dismantling the boundary that had previously separated a free black from a slave, emancipation changed all this. In place of enslaved people, a new and more inclusive subordinate category emerged, one that, being defined by race, did not admit the awkward exceptions and contradictions that manumission had entailed for the peculiar institution of slavery. Emancipation, in short, cancelled out the exemption—you could be an ex-slave but you could not be ex-black. In bringing a form of freedom to black people, the ending of slavery also completed their racialization.

On this basis, it is not surprising that antiblack riots, segregation, and a range of discriminatory practices that foreshadowed the Jim Crow regime should have become established well before the Civil War in northern states that had introduced emancipation. Jim Crow was not to emerge in the South until the 1880s. As James Stewart, Joanne Melish, and other historians have recently documented, however, a new apparatus of discrimination (Stewart terms it "racial modernity") had emerged in the North by the 1830s. Racial modernity deployed a rhetoric of essential and unchangeable racial inferiority to justify an oppressive regime that practically ensured that, though emancipated, black people in the North were by no means equal. Hence the hypothesis that the historical function of race was to restore the inequality that citizenship had theoretically abolished. Race, I wish to suggest, is a pathological by-product of democracy.

Sources Mentioned in Text

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, De Generis Humanae Varietate Nativa: Praemissa Est Epistola Ad Virum Perillustrem Iosephum Banks, 3rd ed. (Göttingen: apud Vandenhoek et Ruprecht, 1795). See also a partial translation in "On the Natural Varieties of Mankind" in T. Bendyshe (ed.), The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach... (London: The Anthropological Society, 1865).

Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: Norton, 1975), especially 1-3, 326-41, 380-7. This work is a classic account of the harmony between the enunciation of revolutionary ideals and the institution of slavery. Morgan had earlier outlined his perspective in an article, "Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox," Journal of American History 59 (1972): 5-29.

Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and "Race" in New England, 1780-1860 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1998), traces and contextualizes the growth and development of racial thought and practice in antebellum New England.

James Brewer Stewart, "The Emergence of Racial Modernity and the Rise of the White North, 1790-1840," Journal of the Early Republic 18 (1998): 181-217 and Stewart, "Modernizing 'Difference': The Political Meanings of Color in the Free States, 1776-1840," Journal of the Early Republic 19 (1999): 691-712. Both articles examine the crisis in racial definitions and race relations that developed in the North in the late 1820s and, as Stewart put it, "exploded in the North during the early 1830s."

Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Free Press, 1994).

Further Reading

This essay extends a perspective that I began to develop in two previous articles, both of which are much denser than this one: Patrick Wolfe, "Land, Labor, and Difference: Elementary Structures of Race," The American Historical Review 106 (2001): 866-905.

______, "Race and Racialisation: Some Thoughts," Postcolonial Studies 5 (2002): 51-62.

There are many general histories of race and racism. An excellent recent account, which deals with racism in the U.S., South Africa, and Nazi Germany, is concise, lucid and a model of comparative scholarship: George M. Fredrickson, Racism: A Short History (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2002).

Kenan Malik, The Meaning of Race: Race, History and Culture in Western Society (New York: New York University Press, 1996), is a sophisticated, clearly written, theoretically informed, and wide-ranging account of the historical career of the idea of race in Western discourse.

George L. Mosse, Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism (Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin University Press, 1978, reprinted 1985) is a clear, authoritative, and passionately argued account of the development of race and racism in European thought from the Enlightenment through Count Gobineau and Houston Stuart Chamberlain to Hitler.

Ivan Hannaford, Race: The History of an Idea in the West (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) is a lengthy but impressively comprehensive account of European discourses on strangers and foreigners from the ancient world to the modern era, presented to sustain the contention that the modern concept of race was a product of the eighteenth century.

Steven J. Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York: Norton, 1981) is an authoritative, lively, incisive account of the presuppositions, follies, and downright distortions that sustained the nineteenth-century obsession with craniology, the bedrock of scientific racism.

Discussions of racial discourse in the U.S. are far too numerous to cite. Most discuss Euroamerican treatment of either black people or Indians. Few discuss them together. Exceptions include Ronald Takaki, Iron Cages: Race and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Knopf, 1979) and Gary Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Peoples of Early North America, 3rd ed. (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1992).

Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1968) is the classic account of European and white American discourses on Africans and the relationship between racial ideologies and slavery. Though no doubt a great work, this book suffers from an oddly ahistorical tendency to attribute white views of Africans to primordial European cultural attitudes to darkness.

Audrey Smedley, Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview, 2nd ed. (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1999), which does not deal with Canada and only tangentially discusses the racialization of Indians, is nonetheless a wide-ranging and well-written synthesis of disciplinary approaches that recounts and invalidates the scientific claims of racial discourse in the U.S.

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1975) is an elegant and impeccably sourced historical elaboration of Morgan's analysis of the contradictory relationship between American ideals of liberty and the persistence of slavery.

Michael A. Morrison and James Brewer Stewart, eds., Race and the Early Republic: Racial Consciousness and Nation-Building in the Early Republic (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002) is an excellent collection of fresh, insightful and innovative essays on a comprehensive range of racial issues in the first half-century following the War of Independence.

Alden T. Vaughan's article "The Origins Debate: Slavery and Racism in Seventeenth-Century Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 97 (1989): 311-54, is a masterful summary of a complex and often acrimonious debate, which preoccupied the American historical profession from the 1950s to the 1970s, over the origins of racial thinking and its relationship to slavery in colonial North America.

David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991) traces the production and maintenance of white consciousness among the white working class in the U.S. In many ways a pioneering work, this book set the scene for a plethora of subsequent studies that showed that, rather than being taken for granted, whiteness had to be carefully articulated and maintained.

Matthew Fry Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998) recounts the fascinating history of how the boundaries of whiteness expanded and shifted in the U.S. as large-scale immigration threatened to blur the boundaries between whites and others.

Jack D. Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples, 2nd ed. (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1993) is a laborious and, in places, overwhelmingly detailed account of the development of racial categories in America, focusing on the classification of people combining Indian and African inheritances. Though a cover-to-cover read is not advisable, the book is an extraordinary repository of information.

Though not interrogating the concept of race, Leon Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961) opened historians' eyes to the mistreatment of African Americans in the antebellum North. As such, it provided a detailed complement to C. Vann Woodward's classic civil rights era text, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), which remains indispensable to an understanding of white discourses on black people in the U.S.

F. James Davis, Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991) presents an exhaustive account of the one-drop rule. Davis overlooks some important counterexamples, though, so his account should be approached with caution. Pauli Murray's compendium, States' Laws on Race and Color, and Appendices (Cincinnati: Women's Division of Christian Service, 1950), can be consulted with confidence.

On white attitudes, law, and policies concerning Indians, the extensive works of Vine Deloria Jr. are apt, authoritative, and informative. See, for instance: Vine Deloria Jr. and David E. Wilkins, Tribes, Treaties, and Constitutional Tribulations (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1999) or Sandra Cadwallader and Vine Deloria Jr., eds., The Aggressions of Civilization: Federal Indian Policy since the 1880s (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984).

Russel Lawrence Barsh and James Youngblood Henderson, The Road: Indian Tribes and Political Liberty (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1980) is a sequential account of the development of Indian law from colonial times up to the 1970s. The analysis is sharp and critical, expressed in economical if somewhat legalistic prose.

The voluminous writings of Francis Paul Prucha are thorough, reliable, and informative. In places, however, Father Prucha's conservatism comes close to apologizing for oppression. See especially his masterwork, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, 2 vols. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska, 1984). See alternatively the 1986 abridged edition.

On the policy of Indian assimilation, Frederick E. Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920 (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1984) is authoritative and lucidly argued. Hoxie also presents a succinctly argued account of the shift in the conceptualization of U.S. citizenship from a collection of equal individuals to a hierarchy of unequal ethnic groups. The classic work on allotment and the Dawes campaign of assimilation is a report that was commissioned by the framers of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934: D. S. Otis, The Dawes Act and the Allotment of Indian Lands, edited by Francis Paul Prucha (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1973), originally published in 1934.

The standard work on the development of the concept of American citizenship from colonial times to the late nineteenth century is James H. Kettner, The Development of American Citizenship, 1608-1870 (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1978), which remains a model of clarity and scholarly thoroughness.

Richard Broome, Aboriginal Australians: Black Responses to White Dominance, 1788-1980, 3rd ed. (Crows Nest, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 2002) is a reliable overview of the shifts in Aboriginal-European relations in Australia from white conquest to the present time.

The best account of Aboriginal people's historical experience of citizenship in Australia is John Chesterman and Brian Galligan, Citizens Without Rights: Aborigines and Australian Citizenship (Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

George Reid Andrews, Blacks and Whites in São Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1988 (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991) is the best English-language account of Afro-Brazilians' experience of and struggle with the problems of citizenship over the century following the ending of slavery and the formation of the Brazilian republic.

An interesting sociological account of the varied ways in which Afro-Brazilians have been classified in modern Brazilian politics is Melissa Nobles, Shades of Citizenship: Race and the Census in Modern Politics (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000).

* The Bell Curve (1994) argued that there are substantial differences in intelligence, not only between individuals but, more controversially, between social groups. The authors' measure of intelligence was the IQ test, which some other scholars have criticized for being weighted in favor of the cultural values of white and higher-class social groups. On the basis of a historical survey of post-World War II IQ test results, however, The Bell Curve claimed that differences in cognitive capacity profoundly affected the working capacity of different groups in modern industrial society. Moreover, these differences resisted remedial programs. IQ, the book claimed, is largely inherited, which meant that IQ differentials between different social groups would remain fairly stable. On this basis, the book noted that black groups in the U.S. scored relatively poorly in IQ tests and associated their relative lack of success in the job market with hereditary cognitive deficiencies.

Patrick Wolfe has written and taught on race, colonialism, and the history of anthropology at the University of Melbourne and Victoria University, Australia. He has been a visiting scholar and presented lectures and seminars at a number of universities in the United States. His current research is a comparative study of race and racialization in the United States, Australia, and Brazil.

Authored by

Patrick Wolfe

University of Melbourne and Victoria University

Melbourne, Australia,