Cold War and Global Hegemony, 1945-1991

We are accustomed to viewing the cold war as a determined and heroic response of the U.S. to communist aggression spearheaded and orchestrated by the Soviet Union. This image was carefully constructed by presidents and their advisers in their memoirs (1). This view also was incorporated in some of the first scholarly works on the cold war, but was then rebutted by a wide variety of revisionist historians who blamed officials in Washington as well as those in Moscow for the origins of the Soviet-American conflict (2).

Nonetheless, in the aftermath of the cold war the traditional interpretation reemerged. John Gaddis, arguably the most eminent historian of the cold war, wrote in the mid-1990s that the cold war was a struggle of good versus evil, of wise and democratic leaders in the West reacting to the crimes and inhumanity of Joseph Stalin, the brutal dictator in the Kremlin (3).

This interpretation places the cold war in a traditional framework. It is one way to understand American foreign policy between the end of World War II and the breakup of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) in 1991. But for quite some time now, historians, political scientists, and economists have been studying the cold war in a much larger global context. They do so because the new documents from the Soviet Union and its former empire as well as older documents from the U.S. and its allies suggest that Stalin conducted a more complex and inconsistent foreign policy than previously imagined and that U.S. officials initially did not regard Stalin, notwithstanding his crimes and brutality, as an unacceptable partner with whom to collaborate in stabilizing and remaking the postwar world.

Most scholars looking at Soviet documents now agree that Stalin had no master plan to spread revolution or conquer the world. He was determined to establish a sphere of influence in eastern Europe where his communist minions would rule. But at the same time, Stalin wanted to get along with his wartime allies in order to control the rebirth of German and Japanese power, which he assumed was inevitable. Consequently, he frequently cautioned communist followers in France, Italy, Greece, and elsewhere to avoid provocative actions that might frighten or antagonize his wartime allies. Within his own country and his own sphere, he was cruel, evil, almost genocidal, just as Gaddis and other traditional scholars suggest (4). Yet U.S. and British officials were initially eager to work with him. They rarely dwelled upon his domestic barbarism. Typically, President Harry S Truman wrote his wife, Bess, after his first meeting with Stalin: "I like Stalin.... He is straightforward. Knows what he wants and will compromise when he can't get it." Typically, W. Averell Harriman, the U.S. ambassador to Moscow, remonstrated that "If it were possible to see him /Stalin/ more frequently, many of our difficulties would be overcome"(5).

Yet the difficulties were not overcome. American fears grew. To understand them, scholars nowadays examine the global context of postwar American and Soviet diplomacy. They see the contest between American freedom and Soviet totalitarianism as part of an evolving fabric of international economic and political conditions in the twentieth century. After World War II, they say, U.S. leaders assumed the role of hegemon, or leader, of the international economy and container of Soviet power. To explain why, scholars examine the operation of the world economy and the distribution of power in the international system. They look at transnational ideological conflict, the disruption of colonial empires, and the rise of revolutionary nationalism in Asia and Africa. They explain the spread of the cold war from Europe to Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America by focusing on decolonization, the rise of newly independent states, and the yearnings of peoples everywhere to modernize their countries and enjoy higher standards of living. Yet the capacity of the U.S. to assume the roles of hegemon, balancer, and container depended on more than its wealth and strength; the success of the U.S. also depended on the appeal of its ideology, the vitality of its institutions, and the attractiveness of its culture of mass consumption—what many scholars nowadays call "soft power" (6).

At the end of World War II, the U.S. and the Soviet Union emerged as the two strongest nations in the world and as exemplars of competing models of political economy. But it was a peculiar bipolarity. The U.S. was incontestably the most powerful nation on the earth. It alone possessed the atomic bomb. It alone possessed a navy that could project power across the oceans and an air force that could reach across the continents. The U.S. was also the richest nation in the world. It possessed two-thirds of the world's gold reserves and three-fourths of its invested capital. Its gross national product was three times that of the Soviet Union and five times that of the United Kingdom. Its wealth had grown enormously during the war while the Soviet Union had been devastated by the occupation by Nazi Germany. Around 27 million inhabitants of the U.S.S.R. died during World War II compared to about 400,000 Americans. The Germans ravished the agricultural economy of Soviet Russia and devastated its mining and transportation infrastructure (7).

Compared to the U.S. in 1945, the Soviet Union was weak. Yet it loomed very large not only in the imagination of U.S. officials, but also in the minds of political leaders throughout the world. It did not loom large because of fears of Soviet military aggression. Contemporary policymakers knew that Stalin did not want war. They did not expect Soviet troops to march across Europe. Yet they feared that Stalin would capitalize on the manifold opportunities of the postwar world: the vacuums of power stemming from the defeat of Germany and Japan; the breakup of colonial empires; popular yearnings for postwar social and economic reform; and widespread disillusionment with the functioning of democratic capitalist economies (8).

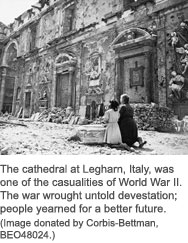

During World War II, the American economy had demonstrated enormous vitality, but many contemporaries wondered whether the world capitalist system could be made to function effectively in peacetime. Its performance during their lifetimes had bred worldwide economic depression, social malaise, political instability, and personal disillusionment. Throughout Europe and Asia, people blamed capitalism for the repetitive cycles of boom and bust and for military conflagrations that brought ruin and despair. Describing conditions at the end of the war, the historian Igor Lukes has written: "Many in Czechoslovakia had come to believe that capitalism... had become obsolete. Influential intellectuals saw the world emerging from the ashes of the war in black and white terms: here was Auschwitz and there was Stalingrad. The former was a byproduct of a crisis in capitalist Europe of the 1930s; the latter stood for the superiority of socialism" (9).

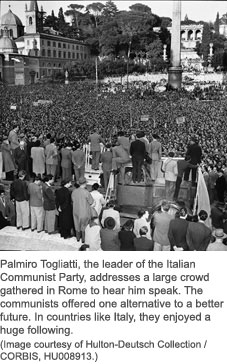

Transnational ideological conflict shaped the cold war. Peoples everywhere yearned for a more secure and better life; they pondered alternative ways of organizing their political and economic affairs. Everywhere, communist parties sought to present themselves as leaders of the resistance against fascism, proponents of socioeconomic reform, and advocates of national self-interest. Their political clout grew quickly as their membership soared, for example, in Greece, from 17,000 in 1935 to 70,000 in 1945; in Czechoslovakia, from 28,000 in May 1945 to 750,000 in September 1945; in Italy, from 5,000 in 1943 to 1,700,000 at the end of 1945 (10). For Stalin and his comrades in Moscow, these grassroots developments provided unsurpassed opportunities; for Truman and his advisers in Washington, they inspired fear and gloom. "There is complete economic, social and political collapse going on in Central Europe, the extent of which is unparalleled in history," wrote Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy in April 1945 (11). The Soviet Union, of course, was not responsible for these conditions. Danger nonetheless inhered in the capacity of the Kremlin to capitalize on them. "The greatest danger to the security of the United States," the CIA concluded in one of its first reports, "is the possibility of economic collapse in Western Europe and the consequent accession to power of Communist elements" (12).

Transnational ideological conflict impelled U.S. officials to take action. They knew they had to restore hope that private markets could function effectively to serve the needs of humankind. People had suffered terribly, Assistant Secretary of State Dean G. Acheson told a congressional committee in 1945. They demanded land reform, nationalization, and social welfare. They believed that governments should take action to alleviate their misery. They felt it "so deeply," said Acheson, "that they will demand that the whole business of state control and state interference shall be pushed further and further" (13).

Policymakers like Acheson and McCloy, the officials who became known as the "Wise Men" of the cold war, understood the causes for the malfunctioning of the capitalist world economy in the interwar years. They were intent on correcting the fundamental weaknesses and vulnerabilities. Long before they envisioned a cold war with the Soviet Union, they labored diligently during 1943 and 1944 to design the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. They urged Congress to reduce U.S. tariffs. They wanted the American people to buy more foreign goods. They knew that foreign nations without sufficient dollars to purchase raw materials and fuel would not be able to recover easily. They realized that governments short of gold and short of dollars would seek to hoard their resources, establish quotas, and regulate the free flow of capital. And they knew that these actions in the years between World War I and World War II had brought about the Great Depression and created the conditions for Nazism, fascism, and totalitarianism to flourish (14).

"Now, as in the year 1920," President Truman declared in early March 1947, "we have reached a turning point in history. National economies have been disrupted by the war. The future is uncertain everywhere. Economic policies are in a state of flux." Governments abroad, the president explained, wanted to regulate trade, save dollars, and promote reconstruction. This was understandable; it was also perilous. Freedom flourished where power was dispersed. But regimentation, Truman warned, was on the march, everywhere. If not stopped abroad, it would force the U.S. to curtail freedom at home. "In this atmosphere of doubt and hesitation," Truman declared, "the decisive factor will be the type of leadership that the United States gives the world." If it did not act decisively, the world capitalist system would flounder, providing yet greater opportunities for Communism to grow and for Soviet strength to accrue. If the U.S. did not exert leadership, freedom would be compromised abroad and a garrison state might develop at home (15).

Open markets and free peoples were inextricably interrelated. To win the transnational ideological conflict, U.S. officials had to make the world capitalist system function effectively. By 1947, they realized the IMF and the World Bank were too new, too inexperienced, and too poorly funded to accomplish the intended results. The U.S. had to assume the responsibility to provide dollars so that other nations had the means to purchase food and fuel and, eventually, to reduce quotas and curtail exchange restrictions. In June 1947, Secretary of State George C. Marshall outlined a new approach, saying the U.S. would provide the funds necessary to promote the reconstruction of Europe. The intent of the Marshall Plan was to provide dollars to likeminded governments in Western Europe so they could continue to grow their economies, employ workers, insure political stability, undercut the appeal of communist parties, and avoid being sucked into an economic orbit dominated by the Soviet Union. U.S. officials wanted European governments to cooperate and pool their resources for the benefit of their collective well-being and for the establishment of a large, integrated market where goods and capital could move freely. In order to do this, the U.S. would incur the responsibility to make the capitalist system operate effectively, at least in those parts of the globe not dominated by the Soviet Union. The U.S. would become the hegemon, or overseer, of the global economy: it would make loans, provide credits, reduce tariffs, and insure currency stability (16).

The success of the Marshall Plan depended on the resuscitation of the coal mines and industries of western Germany (17). Most Europeans feared Germany's revival. Nonetheless, U.S. officials hoped that Stalin would not interfere with efforts to merge the three western zones of Germany, institute currency reform, and create the Federal Republic of Germany. Marshall Plan aid, in fact, initially was offered to Soviet Russia and its allies in eastern Europe. But Stalin would not tolerate the rebuilding of Germany and its prospective integration into a western bloc. Nor would he allow eastern European governments to be drawn into an evolving economic federation based on the free flow of information, capital, and trade. Soviet security would be endangered. Stalin's sphere of influence in eastern Europe would be eroded and his capacity to control the future of German power would be impaired. In late 1947, Stalin cracked down on eastern Europe, encouraged the communist coup in Czechoslovakia, and instigated a new round of purges (18).

Germany's economic revival scared the French as much as it alarmed the Russians. The French feared that Germany would regain power to act autonomously. The French also were afraid that initiatives to revive Germany might provoke a Soviet attack and culminate in another occupation of France. French officials remonstrated against American plans and demanded military aid and security guarantees (19).

The French and other wary Europeans had the capacity to shape their future. They exacted strategic commitments from the U.S. The North Atlantic Treaty was signed in 1949 as a result of their fears about Germany as well as their anxieties about Soviet Russia. U.S. strategic commitments and U.S. troops were part of a double containment strategy, containing the uncertain trajectory of the Federal Republic of Germany as well as the anticipated hostility of the Soviet Union. Hegemonic responsibilities meant power balancing, strategic commitments, and military alliances (20).

Just as western Germany needed to be integrated into a western sphere lest it be sucked into a Soviet orbit, so did Japan. U.S. officials worried that their occupation of Japan might fail and that the Japanese might seek to enhance their own interests by looking to the Soviets or the communist Chinese as future economic partners. In 1948, U.S. policymakers turned their attention from reforming Japanese social and political institutions to promoting economic reconstruction. Japan's past economic growth, they knew, depended on links to Manchuria, China, and Korea, areas increasingly slipping into communist hands. Japan needed alternative sources of raw materials and outlets for her manufactured goods. Studying the functioning of the global capitalist economy, America's cold warriors concluded that the industrial core of northeast Asia, Japan, needed to be integrated with its underdeveloped periphery in southeast Asia, much like Western Europe needed to have access to petroleum in the Middle East (21). It was the obligation of the hegemon of the world capitalist economy to make sure component units of the system could benefit from the operation of the whole.

But, as hegemon, the U.S. also had to be sensitive to the worries and responsive to the needs of other countries. In Asia, as in Europe, many peoples feared the revival of the power of former Axis nations. Truman promised them that U.S. troops would remain in Japan, even as Japan regained its autonomy, and that the U.S. would insure peace in the Pacific, even if it meant a new round of security guarantees, as it did with the Philippines and with Australia and New Zealand (22).

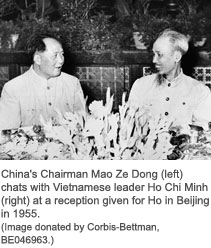

Yet, much as American officials hoped to integrate Japan with Southeast Asia, revolutionary nationalist movements in the region made that prospect uncertain. During World War II, popular independence movements arose in French Indochina and the Netherlands East Indies. Nationalist leaders like Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam and Sukarno in Indonesia wanted to gain control over their countries' future (23). Decolonization was an embedded feature of the postwar international system, propelled by the defeat of Japan and the weakening of traditional European powers. Decolonization fueled the cold war as it provided opportunities for the expansion of communist influence. Third World nationalists wanted to develop, industrialize, and modernize their countries. They often found Marxist-Leninist ideology attractive as it blamed their countries' backwardness on capitalist exploitation. At the same time, the Soviet command economy seemed to provide a model for rapid modernization. Stalin's successors, therefore, saw endless opportunities for expanding their influence in the Third World; leaders in Washington perceived dangers (24).

As hegemon of the free world economy, U.S. officials felt a responsibility to contain revolutionary nationalism and to integrate core and periphery. The Truman administration prodded the Dutch and the French to make concessions to revolutionary nationalists, but often could not shape the outcomes of colonial struggles. When the French, for example, refused to acknowledge Ho Chi Minh's republic of Vietnam and established a puppet government under Bao Dai in 1949, the U.S. chose to support the French. Otherwise, Truman and his advisers feared they would alienate their allies in France and permit a key area to gravitate into a communist orbit where it would be amenable to Chinese or Soviet influence. Falling dominos in Southeast Asia would sever the future economic links between this region and Japan, making rehabilitation in the industrial core of northeast Asia all the more difficult (25).

In the late 1950s and 1960s Japan's extraordinary economic recovery, sparked by the Korean War and fueled by subsequent exports to North America, defied American assumptions. Yet, by then, American officials had locked the U.S. into a position opposing nationalist movements led by communists, like Ho Chi Minh. U.S. officials feared that if they allowed a communist triumph in Indochina, America's credibility with other allies and clients would be shattered. Hegemons needed to retain their credibility. Otherwise, key allies, like Western Germany and Japan, might doubt America's will and reorient themselves in the cold war (26).

Hegemony and credibility required superior military capabilities. Leaders in Washington and Moscow alike believed that perceptions of their relative power position supported risk-taking on behalf of allies and clients in Asia and Africa. In the most important U.S. strategy document of the cold war, NSC 68, Paul Nitze wrote that military power was an "indispensable backdrop" to containment, which he called a "policy of calculated and gradual coercion." To pursue containment in the Third World and erode support for the adversary, the U.S. needed to have superior military force (27). Prior to 1949, the U.S. had a monopoly of atomic weapons. But after the Soviets tested and developed nuclear weapons of their own, U.S. officials believed they needed to augment their arsenal of strategic weapons. Their aim was not only to deter Soviet aggression in the center of Europe, but also to support the ability of the U.S. to intervene in Third World countries without fear of Soviet countermoves.

Nuclear weapons, therefore, produced paradoxical results. Their enormous power kept the cold war from turning into a hot war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Leaders on both sides recognized that such a war would be suicidal. But at the same time nuclear weapons encouraged officials in both Washington and Moscow to engage in risk-taking on the "periphery," that is, in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Caribbean because each side thought (and hoped) that the adversary would not dare to escalate the competition into a nuclear exchange (28). When Ronald Reagan revived the determination of the U.S. to regain military superiority in the 1980s, he sought to use those military capabilities, not for a preemptive attack against the Soviet Union, but as a backdrop to support U.S. interventions on behalf of anti-communist insurgents from Nicaragua and El Salvador to Afghanistan and Angola. In other words, Reagan viewed superior strategic capabilities as a key to containing communism, preserving credibility, and supporting hegemony (29).

For U.S. officials, waging the cold war required the U.S. to win the transnational ideological struggle and to contain Soviet power. To achieve these goals, the U.S. had to be an effective hegemon. This meant that the U.S. had to nurture and lubricate the world economy, build and coopt western Germany and Japan, establish military alliances and preserve allied cohesion, contain revolutionary nationalism, and bind the industrial core of Europe and Asia with the underdeveloped periphery in the Third World. To be effective, Cold Warriors believed that superior military capabilities were an incalculable asset. They focused much less attention and allocated infinitely fewer resources to disseminating their values and promoting their culture. Yet scholars of the cold war increasingly believe that America's success as a hegemon, its capacity to evoke support for its leadership, also depended on the habits and institutions of constitutional governance, the resonance of its liberal and humane values, and the appeal of its free market and mass consumption economy (30).

Endnotes

- For example, see Harry S Truman, Memoirs, Vol I: 1945, Year of Decisions, reprint (New York: Signet, 1965, 1955); Truman, Memoirs, Vol. II: Years of Trial and Hope, 1946-1952, reprint (New York: Signet, 1965, 1956); Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mandate for Change: The White House Years, 1953-1956 (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1963); Dean G. Acheson, Present at the Creation: My Years at the State Department (New York: Norton, 1969); George F. Kennan, Memoirs, 2 vol. paperback ed. (New York: Bantam, 1967-1972).

- See, for example, Joyce and Gabriel Kolko, The Limits of Power: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1945-1954 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972); for a discussion of the different historiographical approaches, see my essay, "The Cold War Over the Cold War," in Gordon Martel, ed., American Foreign Policy Reconsidered, 1890-1993 (London: Routledge, 1994).

- John Lewis Gaddis, We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- For some of the best new scholarship on Stalin, see Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, reprint (New York: Knopf, 2004, 2003); Norman M. Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995); Vojtech Mastny, The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Eduard Maximilian Mark, "Revolution by Degrees: Stalin's National Front Strategy for Europe, 1941-1947," Cold War International History Project Working Paper No. 31 (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2001); Geoffrey Roberts, "Stalin and the Grand Alliance: Public Discourse, Private Dialogues, and the Direction of Soviet Foreign Policy, 1941-1947," Slovo 13 (2001): 1-15.

- Robert H. Ferrell, ed., Dear Bess: The Letters from Harry to Bess Truman, 1910-1959 (New York: Norton, 1983), 522; Harriman to Truman, June 8, 1945, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conference of Berlin: The Potsdam Conference, 1945 (2 vols., Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1960), 1: 61.

- For soft power, see Joseph S. Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004); Nye, The Paradox of American Power: Why the World's Only Superpower Can't Go It Alone (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000 (New York: Random House, 1987), 347-72; R. J. Overy, Russia's War (London: Penguin Books, 1997); Allan M. Winkler, Home Front U.S.A.: America During World War II, 2nd ed. (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2000).

- Melvyn P. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992), 1-141.

- Igor Lukes, "The Czech Road to Communism," in Norman M. Naimark and L. IA. Gibianskii, eds., The Establishment of Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe, 1944-1949 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), 29; William I. Hitchcock, The Struggle for Europe: The Turbulent History of a Divided Continent, 1945 to the Present (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), 1-125.

- Adam Westoby, Communism Since World War II (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1981), 14-5.

- Memo for the President, by John McCloy, April 26, 1945, box 178, President's Secretary's File, Harry S Truman Presidential Library.

- Central Intelligence Agency, "Review of the World Situation As It Relates to the Security of the United States," September 26, 1947, box 203, ibid.

- Testimony by Dean G. Acheson, March 8, 1945, U.S. Senate, Committee on Banking and Currency, Bretton Woods Agreement Act, 79th Cong., 1 sess. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1945), 1: 35.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, The United States in the World Economy (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1943); Harley A. Notter, Postwar Foreign Policy Preparation, 1939-1945 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950), 128; Georg Schild, Bretton Woods and Dumbarton Oaks: American Economic and Political Postwar Planning in the Summer of 1944 (New York: St. Martin's, 1995).

- Harry S Truman, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1947 (Washington, D.C.: U.S.G.P.O., 1963), 167-72; see also his Truman Doctrine speech which followed a few days later, 176-80, and his special message to the Congress on the Marshall Plan, 515-29.

- Michael J. Hogan, The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947-1952 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987); David W. Ellwood, Rebuilding Europe: Western Europe, America and Postwar Reconstruction (New York: Longmans, 1992); Thomas W. Zeiler, Free Trade, Free World; The Advent of GATT (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- John Gimbel, The Origins of the Marshall Plan (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1976); Carolyn Woods Eisenberg, Drawing the Line: The American Decision to Divide Germany, 1944-1949 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- Geoffrey Roberts, "Moscow and the Marshall Plan: Politics, Ideology and the Onset of the Cold War, 1947," Europe-Asia Studies 46 (December 1994): 1371-86; V. M. Zubok and Konstantin Pleshakov, Inside the Kremlin's Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 46-53.

- William I. Hitchcock, France Restored: Cold War Diplomacy and the Quest for Leadership in Europe, 1944-1954 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

- Timothy P. Ireland, Creating the Entangling Alliance: The Origins of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981).

- Michael Schaller, The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Howard B. Schonberger, Aftermath of War: Americans and the Remaking of Japan, 1945-1952 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989); John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 271-3, 525-46.

- Leffler, Preponderance of Power, 346-7, 393-4, 428-32, 464-5; Roger Dingman, "The Diplomacy of Dependency: The Philippines and Peacemaking with Japan," Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27 (September 1986): 307-21; Henry W. Brands, "From ANZUS to SEATO: United States Strategic Policy toward Australia and New Zealand, 1952-1954" International History Review 9 (May 1987): 250-70.

- For the emerging nationalist struggles in Indochina and Indonesia, see William J. Duiker, Sacred War: Nationalism and Revolution in a Divided Vietnam (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995); George McTurnan Kahin, Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952).

- Odd Arne Westad, "The New International History of the Cold War: Three (Possible) Paradigms," Diplomatic History 24 (Fall 2000): 551-65; David C. Engerman, Nils Gilman, Mark H. Haefele, and Michael E. Latham, eds., Staging Growth: Modernization, Development, and the Global Cold War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).

- Mark Atwood Lawrence, "Transnational Coalition-Building and the Making of the Cold War in Indochina, 1947-1949," Diplomatic History 26 (Summer 2002): 453-80; Andrew Jon Rotter, The Path to Vietnam: Origins of the American Commitment to Southeast Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987).

- For the importance of credibility, see the pathbreaking article by Robert J. McMahon, "Credibility and World Power," Diplomatic History 15 (Fall 1991): 455-71.

- NSC 68, "United States Objectives and Programs for National Security," April 14, 1950, in Thomas H. Etzold and John Lewis Gaddis, eds., Containment: Documents on American Policy and Strategy, 1945-1950 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), 401-2; NSC 114/2, "Programs for National Security," October 12, 1951, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1951: National Security Affairs; Foreign Economic Policy (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1979), 1: 187-89.

- For Soviet policy, see A. A. Fursenko and Timothy J. Naftali, "One Hell of a Gamble": Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964 (New York: Norton, 1997); Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, Khrushchev's Cold War (New York: Norton, 2005).

- Peter Schweizer, Reagan's War: The Epic Story of his Forty Year Struggle and Final Triumph Over Communism (New York: Doubleday, 2002).

- G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 163-214; Robert O. Keohane, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), especially 135-81; Michael Mandelbaum, The Ideas that Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy and Free Markets in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Public Affairs Press, 2002); Geir Lundestad, "Empire" by Integration: The United States and European Integration, 1945-1997 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); Gaddis, We Now Know.

Bibliographical Note

Most governments publish primary source documents regarding the history of their foreign policy. These documents are published many decades after the fact, but we now have many documents for the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. For the evolution of the role of the U.S. in the cold war, see U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office); for Britain and the cold war, see Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Documents on British Policy Overseas. Since the end of the cold war, the Cold War International History Project has been publishing (and distributing free of charge) primary source documents from the Soviet Union and other formerly communist nations, including the People's Republic of China. They are indispensable for understanding the global context of the cold war. See the Cold War International History Project, Bulletin (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center, 1992-2004). The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has published several volumes of documents. See, for example, Woodrow J. Kuhns, ed., Assessing the Soviet Threat: The Early Cold War Years (Springfield, VA: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1997); Scott A. Koch, ed., Selected Estimates on the Soviet Union, 1950-1959 (Washington, D.C.: History Staff, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1993); Ben B. Fischer, At Cold War's End: U.S. Intelligence on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, 1989-1991 (Reston, VA: Central Intelligence Agency, 1999).

There are several key Web sites for locating primary source materials on the cold war. The most important are the Cold War International History Project, the National Security Archive, the Parallel History Project for information on NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the Primary Source Microfilm. The Federation of American Scientists also has a Web site with valuable documents on many issues, like the nuclear arms race.

- Cold War International History Project

- The National Security Archive

- The Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact

- Primary Source Microfilm

- Federation of American Scientists

Many U.S. government agencies also have Web sites containing documents on current and past foreign policy.

- U.S. Department of State - Department of Educational and Cultural Affairs

- U.S. Department of Defense

- Central Intelligence Agency

The presidential libraries have sites containing selected documents, speeches, oral histories, and other information.

For short books locating the cold war in a global context, see Robert J. McMahon, The Cold War: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003); David S. Painter, The Cold War: An International History (New York: Routledge, 2002); Geoffrey Roberts, The Soviet Union in World Politics: Coexistence, Revolution and Cold War, 1945-1991; (New York: Routledge, 1999); Geir Lundestad, East, West, North, South: Major Developments in International Relations since 1945, 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Many scholars are now using primary documents from the former Soviet Union and other communist countries to study the cold war. In addition to the books and articles listed in note 3, see David Holloway, Stalin and the Bomb: the Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939-1956 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994); William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York: Norton, 2003); Hope M. Harrison, Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953-1961 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003). Some of the most fascinating books deal with Chinese foreign policy and the relations between Mao Tse-tung and Stalin. See, for example, S. N. Goncharov, John Wilson Lewis, and Litai Xue, Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993); Jian Chen, Mao's China and the Cold War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

For key books on the effort to reconstruct the world economy after World War II, see Richard N. Gardner, Sterling-Dollar Diplomacy in Current Perspective: The Origins and the Prospects of Our International Economic Order (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980); Herman Van der Wee, Prosperity and Upheaval: The World Economy, 1945-1980 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Alfred E. Eckes and Thomas W. Zeiler, Globalization and the American Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

For transnational ideological conflict and the cold war, see Joyce and Gabriel Kolko, The Limits of Power: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1945-1954 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972); Walt W. Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, 3rd. ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); François Furet, The Passing of an Illusion: The Idea of Communism in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Odd Arne Westad, Cold War and Revolution: Soviet-American Rivalry and the Origins of the Chinese Civil War, 1944-1946 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993); Michael E. Latham, Modernization as Ideology: American Social Science and "Nation-Building" in the Kennedy Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); David C. Engerman, Modernization from the Other Shore: American Intellectuals and the Romance of Russian Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003); John Lewis Gaddis, We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

There are some wonderful studies on decolonization, revolutionary nationalism, and the cold war. See, for example, Robert J. McMahon, Colonialism and Cold War: The United States and the Struggle for Indonesian Independence, 1945-49 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981); Frances Gouda and Thijs Brocades Zaalberg, American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2002); Matthew James Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria's Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002); Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). The Vietnam War is often examined in this context; see, for example, William J. Duiker, U.S. Containment Policy and the Conflict in Indochina (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994); George C. Herring, America's Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975, 4th ed. (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2002).

For power and the cold war, see Mark Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); William Curti Wohlforth, The Elusive Balance: Power and Perceptions During the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993); Melvyn P. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992). Raymond L. Garthoff has written two lengthy and illuminating books that link power and ideology. See Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations From Nixon to Reagan (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1985) and The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1994).

For discussions of the end of the cold war that focus on ideas and transnational movements, see Matthew Evangelista, Unarmed Forces: The Transnational Movement to End the Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999); Robert D. English, Russia and the Idea of the West: Gorbachev, Intellectuals, and the End of the Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Lawrence S. Wittner, Toward Nuclear Abolition: A History of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1971 to the Present (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003). For discussions of hegemony and soft power, see the citations in notes 5 and 29.

Melvyn P. Leffler is the Edward Stettinius Professor of American History at The University of Virginia. Currently, he is a Jennings Randolph Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace and holds the Henry Kissinger Chair at the Library of Congress. His book, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford University Press, 1993), won the Bancroft, Ferrell, and Hoover prizes. He is now writing a book about why the Cold War lasted as long as it did and why it ended when it did.

Authored by

Melvyn P. Leffler

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, Virginia